Thursday, October 16, 2008

Epideictic Rhetoric as Acknowledgement: Rhetorical Heroism and Barack Obama’s Speech on Race

Writing about a presidential campaign that is still unfolding is a risky business; every word can be construed as an endorsement of one kind or another. From the outset, let me say that this presentation’s interest in Barack Obama’s speech on race in America should not be taken as an endorsement of his candidacy. Rather, its interest emerges from the simple recognition that Obama’s rhetorical gifts—the likes of which American public discourse has not seen for decades—have drawn attention of many, and that this attention, as well as the considerable disagreement as to what those gifts mean, calls for critical assessment.

The day after Obama spoke in Philadelphia, the editorial board of the New York Times recognized his speech not only for its eloquence but also for its ability to acknowledge the complex reality of race in America. But how should we, as rhetorical scholars, regard his speech? What can it teach us?

This presentation is not a line-by-line analysis of the speech but a reflection on its philosophical and ethical significance, the work it does—or perhaps could be doing—to respond to the ethical call of the public sphere. Its work begins by categorizing Obama’s speech on race in terms of what Aristotle describes as epideictic, the ceremonial rhetoric of praise and blame. Such a categorization seems at first glance to be a strange one, since we are accustomed to seeing epideictic as a sort of catch-all category that deals with the fancy—and often empty—words spoken at ceremonial occasions.

Yet, in many ways, Obama’s speech, occasioned by the remarks of Geraldine Ferraro and the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, who in their various ways brought race to the foreground of his campaign, is indeed an example of epideictic rhetoric. While he certainly mentions his association with Wright and distances himself from his pastor’s controversial comments, Obama’s objective seems to be understanding and expanding the moral dwelling of American public life—what the Greeks would call its ethos—in light of the question of race. Obama seems less interested in exonerating himself or in offering policies to span the racial divide—activities that we would associate with forensic and legislative rhetoric, respectively—than he is in inviting both his critics and his supporters to a new and more constructive public conversation about an issue that continues to divide American public life.

In The Life-Giving Gift of Acknowledgement, Michael Hyde places this sort of communicative labor—what he describes as rhetorical home-making—under the category of epideictic. Epideictic, he contends, invites a community to participate in a new understanding of the world rewoven from its public traditions, sense of identity, and moral texture. Because of its capacity to broaden this public moral texture to include those who have been marginalized, Hyde places epideictic at the center of what he calls rhetorical acknowledgment.

Drawing both from the tradition of the Old Testament and from the thought of Emmanuel Levinas, rhetorical acknowledgement emerges from an existential, pre-communicative awareness of the suffering other: that in eating there are always those who go hungry, that when we belong there are those who will never “belong,” and that we are always our brother and sister’s keeper. To those who call “Where art thou?” in the dark, rhetorical acknowledgment, through the power of epideictic, constantly responds: “Here I am!”

Hyde believes that this epideictic of acknowledgement is a difficult road, carrying the constant risk of contradiction, conflict, and futility. He describes the willingness to embrace this risk as rhetorical heroism. A society without rhetorical heroes is for Hyde a society without an ethos, and a society without an ethos is a society without a home, unable to acknowledge its interconnectedness or articulate the moral obligations of its people to each other. As postmodern American society contends with the very homelessness that Hyde describes, his work encourages us to look for rhetorical heroes, not only in our politicians but also in ourselves.

Hyde’s emphasis on rhetorical acknowledgement and rhetorical heroism is important because it encourages us to encounter Obama’s speech on race on deeper philosophical ground, recognizing race as perhaps the greatest struggle for rhetorical acknowledgement in American history. W. E. B. Du Bois reminds us of how white Americans have struggled (and often failed) to recognize not only the humanity but also the very existence of persons who have lived behind the veil of their black skin, and how black Americans have struggled to articulate what this lack of acknowledgement, this invisibility, has meant.

In interesting ways, Obama enters—one might say embodies—this very crisis throughout his address. As someone with black skin, he identifies with those like Rev. Wright, who are frustrated and angry with American society’s inability to acknowledge America’s racial past. But as someone with a white grandmother who used racial slurs to condemn those who look exactly as he does, he recognizes that he cannot reject those who are frustrated with their own diminishing prospects in a globalized economy. In a Levinasian move, he embraces the contradiction inherent in this experience and, more important, refuses to resolve it. “These people are a part of me,” he says. “And they are a part of America, this country that I love.”

Here, Obama’s understanding of race in America (and, perhaps, America itself) is embedded in the acknowledgment of the existential contradictions inherent within the American experience: between black and white, individual and whole, freedom and responsibilty, self and other. In embracing these burdens, he invites a new political space defined not by cynicism and despair but by the audacity of hope, in which which our engagement with difference and the American Revolution are acknowledged as being one in the same. With Hyde as a guide, we might read the audacity of hope as the audacity of acknowledgement, a politics that begins in the heroic recognition of the contradictions inherent in a homeless world.

Obama’s speech did not, could not, “fix” American race relations, any more than it could lay the issue of race to rest within his own campaign. Yet, Hyde reminds us that to demand such results from rhetorical acknowledgement—or of epideictic, for that matter—is unrealistic. Rhetorical acknowledgement exists merely to open public spaces, and the glory of rhetorical heroism is not applause for the individual but for the tradition that is presented anew. Public life still requires us to enter those public spaces and engage that tradition in constructive ways. That is what forensic and legislative rhetoric are for, and it is unclear whether, for all Obama’s epideictic grandeur, he would be able to marshal those rhetorical resources as president. Yet, while people may disagree as to his candidacy, his speech on race shows the possibilities of epideictic for American public life. When the ethical call of the public sphere is one of homelessness and division, the epideictic of acknowledgement may invite a new beginning.

Wednesday, September 17, 2008

Palin as Rosie the Riveter?

Some in the Republican Party contend that Sarah Palin is the poster child of feminism, the new, "real" face of blue-collar womanhood. And voilà, a button of the Alaska governor in the guise of Rosie the Riveter has appeared for sale on eBay. (Just like her jet!)

Some in the Republican Party contend that Sarah Palin is the poster child of feminism, the new, "real" face of blue-collar womanhood. And voilà, a button of the Alaska governor in the guise of Rosie the Riveter has appeared for sale on eBay. (Just like her jet!)We'll just put aside the fact that she ran Alaska like a Queen Bee out of Mean Girls.

One can quibble that the Republicans' new-found concern for women's issues and sexist representations of women in the media seems, well, a bit cynical. But of course, we can't expect that the right's near-beatification of Palin (“She is anti-abortion, anti-gay-marriage, anti-Big Oil, a lifetime member of the N.R.A., she hunts, she fishes — she is the perfect woman!” says an enthusiast in today's New York Times) would resonate with those who don't believe in beatification at all. (“Go back to the city, you liberal Communists!”)

But in keeping with the hagiography and iconography, I put together a draft of a new campaign poster that could turn the tide:

Friday, September 05, 2008

Will it all come down to Colorado?

But the CBS poll reflects only the national popular vote, which is, of course, completely meaningless in the American Electoral College. There, too, we're in for a ride.

Take, for instance, Karl Rove's recent breakdown of the swing states as of September 3:

Here, Obama leads 260 to 194 in the Electoral College, with only 84 electoral votes in play.

Here, Obama leads 260 to 194 in the Electoral College, with only 84 electoral votes in play.

Assuming that the map stays as it is, the good news for Obama is that if he wins Ohio, Virginia, or Florida or a combination of New Hampshire and the states in the American West, he's in. But given this electoral map, McCain's choice of Palin starts to make sense. As a evangelical, frontier-state governor, she can campaign strongly in western states, and as a pro-life Christian feminist, she may be able to energize Christian conservatives in Ohio, Virginia, and Florida, perhaps enough to tip the scales away from Obama. That leaves only New Hampshire in the Obama column, which leaves him short.

The McCain-Palin strategy is this: Win by forcing Obama to lose. And it could pay off.

Take a look at today's electoral map from Politico.com, which has Obama winning the Electoral College 273-265:

So it's going to be close. A nail-biter, decided late in the night, and perhaps early the following morning.

Thursday, August 28, 2008

Obama's speech

- Is it going to rain? (Luckily—and more than a few PR folks are going to be breathing a sigh of relief—no.)

- Is it going to come off the way Obama wants it to? (A much more difficult question.)

Peter Gage, one of the Obama planners, said he studied photographs of Kennedy’s speech at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, the only other such address to be held in an outdoor stadium in the modern television era.Now that rain is out of the forecast, Obama's aides are buzzing about the technical details of the speech: Will it make Obama look elitist? Will the "Temple of Obama" backdrop constructed by party staffers to make him look "presidential" make him look narcissistic instead? Will he sound like he is talking out of a tin can? Will the strategy of having all of the people in the stadium send text messages—a tactic that seems too cute by half—crash the cell phone system?

Mr. Gage said the circular stage in Denver was inspired by Kennedy’s. A Sky Cam above the field will provide bird’s-eye views. Mr. Obama’s family will sit on seats on the floor before him, along with voters from swing states. The goal is to highlight ordinary people, and then mobilize them to work for the campaign.

The concern here is that the speech risks becoming a technical event instead of a rhetorical one. Is the Obama campaign as worried about what he will say in his speech as they are about packaging its scene? Certainly, the tone and presentation of the address are going to be essential to its reception—and a gaffe here would no doubt be serious and repeated throughout the campaign—but few remember what JFK looked like when he spoke. They remember what he said, how he captured the imagination of an uncertain, post-war America with a vision of a new possibilities, and how his speech transformed a presidency into Camelot.

Wednesday, August 27, 2008

Pittsburgh, the fifth-poorest city?

Median income is $32,363, though this figure may be inflated because of the presence of wealthy neighborhoods. The national median income is $50,740, or a little over 1.5 times that of the typical Pittsburgher.

In an interesting example of how a statistical picture can change depending on the scope of the data surveyed, the Tribune-Review's article on the same census report completely omits the city's overall ranking in comparison to other major cities and instead looks at Allegheny County itself, where the median income has actually risen 3.3 percent since 2006 to $46,401.

Where the Post-Gazette finds despair in the wings:

"With $4-a-gallon milk prices and history-making high gas prices, we need policy makers to focus on health and economic policies that create jobs, reduce poverty and provide access to health care for all to strengthen families," said the Rev. Neil Harrison, executive director of Lutheran Advocacy Ministry in Pennsylvania.The Tribune-Review finds reason to celebrate:

"I think it's generally good news for the region," said Harold Miller, president of Future Strategies, a Downtown management consulting firm.While the median income remains above the 2008 federal poverty guidelines (and, in the case of Allegheny County, well above the poverty guidelines), the income figures don't look as good when compared to what Diana Pearce calls the “self-sufficiency standard”: the minimum income a household needs to live on its own without help from public or private charity.

While Pearce's measurements are subjective and controversial, they are important in establishing the gap between the desperately poor and what is often called "the working poor," the folks who work hard—often at more than one job—but are always falling behind. The 2008 version of her report for Pennsylvania suggests that while a single person with a child earning Pittsburgh's median income would be barely self-sufficient, anyone else would be struggling:

1 adult, 1 schoolage child: $31,075In contrast, Allegheny County, with the exclusion of Pittsburgh, has much different—and much better—numbers:

1 adult, 1 preschooler, 1 schoolage child: $44,849

2 adults, 1 preschooler, 1 schoolage child: $49,573

1 adult, 1 schoolage child: $33,315Taken together, the stories and statistics suggest an extraordinary and growing disconnect between the city and the surrounding county in terms of both economics and overall perspective: Residents of Ross Township, which borders the city, recently lost a bitter dispute over a housing development designed for people making $24,800 and $37,200 a year, which just so happens to be the income of the typical Pittsburgher. And the conflict between the city and the surrounding county is only likely to get worse as Pittsburgh gets poorer and looks to its region for help.

1 adult, 1 preschooler, 1 schoolage child: $46,184

2 adults, 1 preschooler, 1 schoolage child: $52,958

Tuesday, August 26, 2008

David Brooks gets it right

The same seems to be true for this week, as the Democratic convention seeks to launch Obama down the road to the White House. While he recognizes Obama's dip in the polls, Brooks urges Obama not to give into the Democratic advice-mongers and chattering classes who want him to change directions. This is good advice, and not just because the same folks who are urging Obama to change are the same ones who sent Stevenson, Humphrey, McGovern, Mondale, Dukakis, Gore, and Kerry into the toilet. It's because Obama represents a completely different sort of politics:

At the core, Obama’s best message has always been this: He is unconnected with the tired old fights that constrict our politics. He is in tune with a new era. He has very little experience but a lot of potential. He does not have big achievements, but he is authentically the sort of person who emerges in a multicultural, globalized age. He is therefore naturally in step with the problems that will confront us in the years to come.This is Obama's brand, and while Brooks may not buy into it, he understands its importance. The Clintons were candidates of late modernity, providing triangulating wonkish solutions to the American post-industrial bureaucracy. Obama is a postmodern candidate—Brooks says as much in calling him "the 21st century man"—and his candidacy's strength lies in the ways that it speaks to the new age of media and culture. Obama has such a following amoung younger Americans precisely because he emerges out of their cultural context, but this strength among younger voters can translate as a weakness for those who are uncomfortable or unfamiliar with what is often called "the postmodern turn," which is at once style-driven, image conscious, technologically saavy, and fluid.

For instance, the concern over establishing Obama's identity among voters—who he "is"—is in many ways an attempt to force a modern answer onto a postmodern question. Within a modern perspective, identity is a fixed issue and part and parcel with personhood. If one has no "identity," one is not a person, and to refuse to declare an identity seems both strange and disturbing. On the other hand, postmodernity rejects the notion of a fixed identity altogether and instead leaves it as a perpetually open question.

The slipperyness with which Obama treats his understanding of his own identity—it's unclear whether he himself knows who he "is"—reflects the postmodern milieu. To force an identity on him—whether it be a wonk, populist, or a fighter—as many Democratic pundits are doing is to provide a response that is, in many ways, culturally out of date. Postmodern politics is not concerned about identity but is constantly transcendent and constructive, acknowledging differences and seeking spaces of common ground. This is the politics that Obama owns, and this is the politics that he should pursue. As Brooks says:

So as I’m trying to measure the effectiveness of this convention, I’ll be jotting down a little minus mark every time I hear a theme that muddies that image. I’ll jot down a minus every time I hear the old class conflict, and the old culture war themes. I’ll jot down a minus when I see the old Bush obsession rearing its head, which is not part of his natural persona. I’ll write a demerit every time I hear the rich played off against the poor, undercutting Obama’s One America dream.Brooks gave good marks for last night. Whether the rest of the convention will continue to play out that way is anyone's guess.

I’ll put a plus down every time a speaker says that McCain is a good man who happens to be out of step with the times. I’ll put a plus down every time a speaker says that a multipolar world demands a softer international touch. I’ll put a plus down when a speaker says the old free market policies worked fine in the 20th century, but no longer seem to be working today. These are arguments that reinforce Obama’s identity as a 21st-century man.

Monday, August 25, 2008

The coolness of civic republicanism

From the perspective of many, the stigma of a celebrity candidacy is something to be overcome, and if celebrity is confused with stupidity or vacuousness—style over substance, as Cicero would put it—it certainly is. But over the weekend, Matt Bai in the New York Times Magazine suggested that celebrity and the presidency are not mutually exclusive.

Who’s to say that Americans are misguided for craving a little cool in their candidates? It’s not simply that ours is a country of celebrity-seeking robots (although there may be some truth to that as well). Perhaps it’s more that Americans are weary of a political system that has all but ground to a halt, and every four years they search for the galvanizing personality who stands a chance of dislodging it. The infatuation with star quality reflects, on some level, the yearning for the next Roosevelt (Theodore or Franklin) or Kennedy (John or Robert), some reformer with the dynamism and charisma to renew dialogue at home and kinships around the world, to tell us the truths we need to hear without telegraphing defeat.Bai isn't describing something new but rather a fundamental aspect of the tradition of American political rhetoric that, in many ways, we have forgotten. Throughout the nineteenth century, American presidents and politicians—Abraham Lincoln, Daniel Webster, William Jennings Bryan—drew from the tradition of the rhetoric of the Roman Republic, particularly the rhetoric of Cicero. This rhetorical style, what Robert Hariman describes in terms of civic republicanism, idealized politicians who stood "in the breach" of history in the service of the republic.

The best politicians in the civic republican tradition (whether they were Cicero fighting to preserve Roman government against Ceasar's dictatorship, Lincoln defending the principles of the Union, Bryan trying to keep farmers from being crucified "upon a cross of gold" by the gold standard, or FDR flying to speak to the Democratic National Convention when getting on a plane was considered both unprecedented and dangerous) took on the status of cultural heroes, demigods in the political pantheon, the ultimate of "cool." Of course, civic republican orators, like all celebrities, certainly tended toward egocentrism—no one could have accused Cicero of humility, for instance—but theirs was an egocentrism with the country at heart.

So Obama's sweeping rhetorical prowess is in many ways actually the norm of American politics, not the exception. Celebrity has always been a part of American politics. If Obama stands out as unusual, it is because American presidents have moved away from the civic republican tradition, becoming more managerial and policy-centered instead. As long as Obama stands within the civic republican tradition—speaking to American ideals, bridging the gaps between ideological divisions, emphasizing substance instead of style—he should not be confused with another Paris Hilton or Britney Spears, as a "celebrity" in the crassest sense. Rather, he should be understood as following in a deeper American tradition in which sweeping, grand rhetoric was placed fully in the service of the republic. With Obama, the old has become new again.

Friday, August 22, 2008

Was Gorbachev right?

The news coverage has been far from fair and balanced, especially during the first days of the crisis. Tskhinvali was in smoking ruins and thousands of people were fleeing—before any Russian troops arrived. Yet Russia was already being accused of aggression; news reports were often an embarrassing recitation of the Georgian leader’s deceptive statements.Of course, these are controversial words, and given what seemed to be the grossly disproportionate nature of the Russian response to the Georgian situation, Gorbachev seems at some level to be defending the indefensible. But judging from the reactions on the New York Times's website, the biggest problem with Gorbachev's argument from the American perspective is that he actually has a point.

It is still not quite clear whether the West was aware of Mr. Saakashvili’s plans to invade South Ossetia, and this is a serious matter. What is clear is that Western assistance in training Georgian troops and shipping large supplies of arms had been pushing the region toward war rather than peace.

While the Russian response indeed presents a variety of ethical problems from the perspective of just war theory, the fact remains that the Georgian government and its president, Mikheil Saakashvili, precipitated the conflict by attacking first. One can certainly argue that the Georgians could have been goaded or tricked by Russia into attacking, and this may have been the case. Nevertheless, it is the responsibility of any government to avoid senseless wars that it cannot ever hope to win, and even Georgia's allies in Europe are increasingly seeing Saakashvili's misadventure in South Ossetia as either grossly misinformed or galactically incompetent. The reluctance of American media to broach this topic is profoundly problematic, and Gorbachev is right in pointing it out.

Moreover, Gorbachev's column also reiterates the point that the American policy toward Russia has not gotten over the Cold War, ranging from being blatantly patronizing on the one hand (e.g., forcing American missile defense down the Russian's throats as if they didn't exist) to being unreflectively alarmist on the other (e.g., seeing Russia as a rogue nation bent on destabilizing the world). The New York Times today reports that the Russian bear is once again keeping Washington policy-makers up at nights.

Again, the United States may be perfectly warranted in responding as it has. Nevertheless, making Russia into a pariah state and placing it into the category of Iran, Syria, and others also seems to be something of a self-fulfilling prophecy that doesn't give us many constructive policy options.

“Outrage is not a policy,” said Strobe Talbott, who was deputy secretary of state under President Clinton and is now the president of the Brookings Institution. “Worry is not a policy. Indignation is not a policy. Even though outrage, worry and indignation are all appropriate in this situation, they shouldn’t be mistaken for policy and they shouldn’t be mistaken for strategy.”

Thursday, August 21, 2008

College education vs. certification

Murray's solution: Certification exams to level the playing field, allowing students from a variety of educational backgrounds to verify that they have achieved the standard set of knowledge and skills necessary to participate in the economy.

For a neoliberal like Murray, who researches for the American Enterprise Institute, this is a shocking admission. No less than Milton Friedman rejected the idea of certification barriers as being economically inefficient, because they artificially restrict the supply of certified workers (e.g., lawyers) to a select few who have the wherewithal to cross the certification barriers. And by restricting supply, certification both raises the costs of those services and often forces those who are have not been certified but who are otherwise perfectly able to provide those services out of the market altogether.

Murray's point, of course, is not that certification is perfectly efficient but rather that it is more efficient than the experience of earning—or failing to earn—a bachelor's degree, which now serves as a highly variable (and, for Murray, often misleading) basic qualification for the job market.

Higher education does vary in quality, as do students. But does that mean that we need a certification system? Should the certification process be company-specific, industry-specific, or somehow controlled by the state? And what constitutes "certification" in the first place? Murray favors a nationalized approach:

No technical barriers stand in the way of evolving toward a system where certification tests would replace the BA. Hundreds of certification tests already exist, for everything from building code inspectors to advanced medical specialties. The problem is a shortage of tests that are nationally accepted, like the CPA exam.Yet, in making a proposal for nationalization, Murray is violating his own neoliberal logic. The strength of neoliberal economics is its recognition that the marketplace, not the state, needs to be in control of a people's economic destiny. Creating a series of nationalized tests would not reduce the educational bureaucracy but merely re-create it under a national banner. What is more, the decision as to what constitutes certification and education is removed from the hands of individuals and companies, and this presents significant problems in a diverse country that can't decide whether or not something like evolution should be taught.

But when so many of the players would benefit, a market opportunity exists. If a high-profile testing company such as the Educational Testing Service were to reach a strategic decision to create definitive certification tests, it could coordinate with major employers, professional groups and nontraditional universities to make its tests the gold standard. A handful of key decisions could produce a tipping effect. Imagine if Microsoft announced it would henceforth require scores on a certain battery of certification tests from all of its programming applicants. Scores on that battery would acquire instant credibility for programming job applicants throughout the industry.

What if one group objects to a particular body of knowledge as being immoral? What if a company's needs are different from the rest of the industry, requiring a more complex set of examinations? How will certification standards change? What would this mean for education itself, once it is pursued merely as a set of "skills" instead of an intrinsic pursuit of a well-rounded life? And how can we quantify "transferable skills" like organizational abilities, the ability to learn, or interpersonal sensitivity?

In addition, in citing Microsoft as an example, he ignores the ways that many companies, particularly in the technology sector, already police themselves through arduous interview processes and certification standards for their own products. This is the grassroots effort that a neoliberal would admire, because it preserves the freedom of individuals to choose how—or whether—to prepare themselves for work and of companies to decide what those qualifications should be.

Wednesday, August 20, 2008

Drafting Caroline Kennedy?

For Moore, an Obama-Kennedy ticket is a deeply emotional issue, tied to his own populist vision of America. The other candidates—Senator Joe Biden of Delaware, Senator Evan Bayh of Indiana, and Governor Tim Kaine of Virginia—are too old school, and too responsible for voting for "that war," to be worthy of Obama's idealistic potential. In contrast, Kennedy, the last surviving link to the Camelot that was the Kennedy years, gives the ticket the idealistic power-punch Moore believes it needs.

What Obama needs is a vice presidential candidate who is NOT a professional politician, but someone who is well-known and beloved by people across the political spectrum; someone who, like Obama, spoke out against the war; someone who has a good and generous heart, who will be cheered by the rest of the world; someone whom we've known and loved and admired all our lives and who has dedicated her life to public service and to the greater good for all.But there are several concerns with Moore's proposal:

- Kennedy has to want to be vice president, and as Moore acknowledges, she has scrupulously avoided political life.

- Obama is running for the presidency of the United States of America, not the United States of Michael Moore, which means that he is going to need to find a way to broaden his ticket. Of course, Moore's appeal may also reflect the concerns of the American Left, who have become worried that Obama may not be the liberal messiah they have been hoping for.

- The Obama campaign is already a "dream ticket," regardless of whom he puts on the ballot. Putting Kennedy on a ticket that is already laden with the hopes and ideals of a generation would push it over the edge and run the risk of transforming Obama into another Adlai Stevenson. (Who, as the Clintons think, he may already be.)

- Obama's choice should be a pragmatic decision that helps address his weaknesses.

Personally, I think that the top three are all weak, though Tim Kaine—a change-oriented, moderate Catholic with some (but not much) executive experience—is probably the best of the three.

Though, I'm biased: My pick, since February, has been Bill Richardson.

Tuesday, August 19, 2008

Obama and McCain on a debate

First, the candidates' desire for exposure and the news media's desire for ratings created a viscious circle that created a carnivalesque atmosphere. Because neither party had an incumbent or an "heir apparent"—who would have both the incentive and the authority to keep primary debates to a minimum—all of the candidates in both parties were scrambling to get into as many forums as possible, both on network and cable news and on less traditional stages like Logo. And because there were so many competing programs, the journalists who served as debate moderators constantly had to push the envelope in their questions. Money quote:

The amazing part of this process was the sheer indignity of it. All eight of these people [the Democratic candidates] had been public officials. Odds were that one among them would be the next president of the United States. Yet they compliantly held up their hands like grade-schoolers or contestants on Fear Factor. While candidates are subjected to almost everything during a long primary season and are used to skepticism and outright hostility from the press, serving as game-show props represented something new.Second, while Obama is a far weaker debater than he is an orator—“You’ve got to remember, he is a constitutional-law professor” says Newton Minow, the former chairman of the Federal Communications Commission who had once hired Obama as a summer associate while a partner at the law firm Sidley Austin—he can get better and sharper given enough time. Indeed, Fallows points to 2004, in which Obama was relaxed and sharp during his Senate race against Alan Keyes, as showing Obama's potential. Money quote:

The Obama of 2004 didn’t spend much time on his now-familiar “new age of politics” theme (or need to). If asked about steel-industry jobs, tax rates, or the death penalty, he would address the specifics of those issues, without bothering to stress the need for Americans to bridge their partisan divides. Every now and then, he would make those larger points—after all, this was six weeks after his famous speech at the Democratic convention about moving past red states and blue states, to the United States of America. But they seemed incidental rather than central.Third, the presidential debates seem to be as much about style as they are about the ability to make arguments. This is a subtle point that Fallows seems to miss. Both George W. Bush and Obama made significant changes to their debating style when they entered the presidential race. Fallows notes that Bush was a "silver-tongued Texas politician" as governor who, as president, seemed to be afflicted by some sort of aphasia, in which he seemed to be consciously dumbing-down his debating style, perhaps to make his far-more skilled opponents look arrogant and elitist in the eyes of his working-class, Christian base. Similarly, Obama's debating has become much more serious as a presidential candidate, perhaps because he has framed his candidacy in such a serious, civic republican way.

That previous Obama also sounded very little like a professor. With dismissive ease, he reeled off rebuttal points and identified errors as if he had been working in a courtroom rather than a classroom all his life. Keyes had said that Jesus Christ would not have voted for Obama. Obama was asked for his response: “Well, you know, my first reaction was, I actually wanted to find out who Mr. Keyes’s pollster was, because if I had the opportunity to talk to Jesus Christ, I’d be asking something much more important than this Senate race. I’d want to know whether I was going up, or down.”

All in all, Obama seemed in his element and having fun—two things no one has detected about his debate performances this past year.

Fallows believes that Obama has to come out like the relaxed firebrand that he was in 2004 to succeed in this year's debates, but this may backfire because it would play against his "brand." It may be better for him to play it cool, find ways to sharpen his answers, and rely on the fact that McCain is probably going to fare worse in the debates than he will.

Monday, August 18, 2008

The Daily Show

This weekend, the New York Times ran an article by Michiko Kakutani on Jon Stewart and "The Daily Show," noting a 2007 survey by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press that found he was tied with Dan Rather, Tom Brokaw, Brian Williams, and Anderson Cooper as the fourth most admired newscaster in America.

Which should come as a surprise, since he isn't technically a newscaster, or even a journalist.

One can see the success and cultural importance of "The Daily Show" as signaling the death of serious journalism and the death of the American public discourse. Of course, there's some merit to these concerns, and Stewart would probably share them. But one can also see "The Daily Show" as reflective of a broader trend in cultural production and engagement. The state of American public discourse, in this view, isn't any worse than it has been in the past, but is merely changing, and in many ways "The Daily Show" can be viewed as a constructive response to these changes.

I say this for three reasons:

First, "The Daily Show," unlike the emotivistic exchanges that often dominate American popular culture, can be seen as operating from the same standpoint of humane cultural criticism that has been central to Western intellectual life since Montaigne. For example, "for all its eviscerations of the administration, 'The Daily Show' is animated not by partisanship but by a deep mistrust of all ideology," Kakutani writes. "A sane voice in a noisy red-blue echo chamber, Mr. Stewart displays an impatience with the platitudes of both the right and the left and a disdain for commentators who, as he made clear in a famous 2004 appearance on CNN’s 'Crossfire,' parrot party-line talking points and engage in knee-jerk shouting matches."

Stewart's commitment to constructive discourse—a commitment that allows him to say "why I grieve but why I don’t despair"—reflects a sentiment that Montaigne would share.

Second, "The Daily Show" reflects the ways that information needs are changing. "The Daily Show" is not a news program but a program in which information is discussed and made understandable. That "The Daily Show" is understood to be the only news source of many young Americans is a problem. But the program assumes that people already know the basic headlines; it fact, it wouldn't succeed as a comedy show if it didn't. Rather, it makes its money by condensing the echo chamber of contemporary media—from 15 TiVos, no less—into an intelligible, meaningful half-hour.

Third, "The Daily Show" shows that humor is a tool for the constructive engagement of social problems. Of course, laughter can sometimes be deconstructive and cynical, designed to humiliate the other or mask a sense of destructive bitterness. But Stewart's program works because it uses humor to ask questions about the constant stream of cultural production in which American life is situated. But Stewart's questions are more subtle and are interested in finding a place to stand within the confusion. Cynical humor laughs at the darkness, constructive humor seeks to find a foothold to climb out of it.

Friday, August 15, 2008

Speechless

- This is humiliating to the entire discipline of communication and rhetorical studies. Reid-Brinkley and Shanahan come from two of the top departments in the field (Georgia and UT Austin, respectively), and Reid-Brinkley teaches in one of the top departments in the field. Quite simply, these people are supposed to reflect the best that the field has to offer, which scares me.

- The discipline of debate and argumentation is not about winning arguments and tournaments. It's about learning how to make and defend arguments—especially difficult and controversial arguments—with respect and civility. Both instructors have failed in the most categorical way possible.

- Having an advanced degree is not the same as having emotional maturity. In fact, graduate education may hinder people from developing the human skills necessary to survive in the world. (Incidentally, priestly formation in Catholicism emphasizes human formation in addition to pastoral, intellectual, and spiritual formation. Perhaps graduate education should similarly add human dimensions to its educational programs.)

- There's an edited book in here somewhere. Scholars in the field need to engage this issue, not to condemn it but to find ways out of it.

Thursday, August 14, 2008

Corsi's confabulation

But this book isn't anything like its predecessor. Nope. We know this because Corsi says so in his preface (reprinted on the New York Times website):

Any implication that this book is a “Swift Boat” book is not accurate in that John O’Neill and the other members of the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth have had nothing to do with this book, its analysis and arguments, or my opposition to Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign.It's just "Swift Boat"-like.

As I thought about the appearance of Corsi's book, which I will never read, I thought about the problem of what philosopher Sissela Bok calls confabulations, stories where truth and lies are so closely interwoven that no one can tell the difference between the two.

In the case of Corsi's confabulation, he finds the hidden prejudices of his target audience (which, admittedly, aren't hard to spot) and then dumps so many disembodied "facts" on those prejudices that it's impossible for anyone to fact-check what he says. Of course, Corsi, whose academic pedigree is prominently displayed on the title, postures as if he is producing real research. "My intent in writing this book," he says, "is to fully document all arguments and contentions I make, extensively footnoting all references, so readers can determine for themselves the truth and validity of the factual claims." Yet, as with Unfit for Command, his narrative is full of cherry-picked quotations, innuendos, and bold-face lies.

Even so, the power of his story comes not from the fact that it "hangs together" (what rhetorical scholar Walter Fisher calls narrative coherence) under scrutiny, but from the fact that it coheres just enough that it plays into the biases the audience already brings to the text. For these folks, who are already pretty much convinced that Obama is a radical leftist and probably an Islamist Manchurian candidate to boot, Corsi's book will mysteriously "ring true" (the quality of narrative that Fisher describes as narrative fidelity). And therein lies its power.

From a public relations perspective, the problem with confabulations like this, whether they are called Unfit for Command or The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk, is that they are the mutant viruses of public discourse. Once they are out in the public conversation—and especially when they are put in print in a best-selling book—they are often there to stay. You may be able to defeat them, but they will always come back in a different form. Obama's team is much more proactive than Kerry's was, but it's unclear how effective they will be.

Wednesday, August 13, 2008

Because high school is supposed to suck

But white folks have nothing on South Koreans. The cram culture of South Korean high schools, Choe Sang-Hun reports in the New York Times this morning, makes suicide the second highest cause of death among teens in that country. The South Korean college entrance exams are brutal, and because going to particular schools tracks a person for life, students face immense pressure to do well.

But if you don't get into the college of your choice, there's always SUPER CRAM SCHOOL! Which is like high school would be like if you were in prison, in the military, or a Republican:

Jongro [the school profiled in the piece] opened last year. Its four-story main building houses classrooms and dormitories, with eight beds per room. The school day begins at 6:30 a.m., when whistles pierce the quiet and teachers stride the hallways, shouting, “Wake up!”Wimps. That's not what it was like in the good old days:

After exercise and breakfast, the students are in their classrooms by 7:30, 30 per class. Each room includes a few music stands, for students who stand to keep from dozing.

A final roll call comes at 12:30 a.m., after which students may go to bed, unless they opt to cram more, until 2:00 a.m.

The routine relaxes on Saturday and Sunday, when students have an extra hour to sleep and two hours of free time. Every three weeks the students may leave the campus for two nights.

The curriculum has no room for romance. Notices enumerate the forbidden behavior: any conversation between boys and girls that is unrelated to study; exchanging romantic notes; hugging, hooking arms or other physical contact. Punishment includes cleaning a classroom or restroom or even expulsion.

Kim Sung-woo, 32, who teaches at Jongro, remembered the even more spartan regimen of the cram school that he attended. In his day, he said, students desperate for a break slipped off campus at night by climbing walls topped with barbed wire. Corporal punishment was common.Now that's an education.

Tuesday, August 12, 2008

Postmortem on Hillary

The first was that, outward appearances notwithstanding, the campaign prepared a clear strategy and did considerable planning. It sweated the large themes (Clinton’s late-in-the-game emergence as a blue-collar champion had been the idea all along) and the small details (campaign staffers in Portland, Oregon, kept tabs on Monica Lewinsky, who lived there, to avoid any surprise encounters). The second was the thought: Wow, it was even worse than I’d imagined! The anger and toxic obsessions overwhelmed even the most reserved Beltway wise men. Surprisingly, Clinton herself, when pressed, was her own shrewdest strategist, a role that had never been her strong suit in the White House. But her advisers couldn’t execute strategy; they routinely attacked and undermined each other, and Clinton never forced a resolution. Major decisions would be put off for weeks until suddenly she would erupt, driving her staff to panic and misfire.Yet, I feel for Clinton and her team. They did have a plan, and it was a good plan. The problem was that it wasn't good enough, and no one could figure out how to crack the Obama code. (And to be fair, I'm not sure how I would have cracked the Obama code, either.) But in the moment of confusion, Clinton made the biggest mistake of all: She started beating her staff.

Above all, this irony emerges: Clinton ran on the basis of managerial competence—on her capacity, as she liked to put it, to “do the job from Day One.” In fact, she never behaved like a chief executive, and her own staff proved to be her Achilles’ heel. What is clear from the internal documents is that Clinton’s loss derived not from any specific decision she made but rather from the preponderance of the many she did not make. Her hesitancy and habit of avoiding hard choices exacted a price that eventually sank her chances at the presidency.

Not that the staff didn't deserve a beating, of course, but here they needed a sense of direction and leadership that only Clinton herself could have provided. She was the one who hired Mark Penn, she was the one who ultimately decided on the direction of the campaign, and she needed to be the one who righted it. But she didn't. And so she lost.In the hours after she finished third in Iowa, on January 3, Clinton seized control of her campaign, even as her advisers continued fighting about whether to go negative. The next morning’s conference call began with awkward silence, and then Penn recapped the damage and mumbled something about how badly they’d been hurt by young voters.

Mustering enthusiasm, Clinton declared that the campaign was mistaken not to have competed harder for the youth vote and that—overruling her New Hampshire staff—she would take questions at town-hall meetings designed to draw comparative,” but not negative, contrasts with Obama. Hearing little response, Clinton began to grow angry, according to a participant’s notes. She complained of being outmaneuvered in Iowa and being painted as the establishment candidate. The race, she insisted, now had “three front-runners.” More silence ensued. “This has been a very instructive call, talking to myself,” she snapped, and hung up.

She could have won, but this campaign is not about competence in running the federal bureaucracy but about vision. Americans are uncertain about the new world where they now find themselves: a world of terrorism, a shrinking middle class, a plugger economy, and environmental uncertainty. They don't want a policy wonk who can give them better policy programs. They want a visionary who can help them understand what those policies and programs mean. Or, as Obama put it: “It’s true that speeches don’t solve all problems. But what is also true if we cannot inspire the country to believe again, it doesn’t matter how many policies and plans we have.”

Obama has given his vision, but McCain still hasn't. And if he can't, he'll have a Hillary problem, too.

Monday, August 11, 2008

Georgia on my mind

Late last week, when fighting erupted between Russia and Georgia over the disputed regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, there were some concerns as to who, exactly, was the aggressor. Were Georgian forces moving into those regions to restore order, or were they, as the Russians claimed, perpetrating genocide? Or was Russia using humanitarian concerns as a pretext to force a democracy that was leaning too far to the West into subjugation?

The consensus (in the West, at least) seems to be that Russia is the aggressor—Russia has been overtly hostile to Georgia for years and has imposed sanctions, including natural gas, designed to starve the country into submission—but there seems to have been slow preparations for hostilities on both sides. Such preparation would account for how quickly hostilities rose to their current levels of violence.

If Georgia did prepare for—and perhaps even expected—conflict, this raises significant questions: If they had no hope of winning (other than by waging war to arouse the anger of the West), why did Georgia even consider military action as being a viable option in the first place? Is this a desperate act of a desperate people, or did the West promise to help?

In some ways, neither side seems to be fighting a purely just war. Of the two, of course, Russia has a much harder case to make, since Russia's sanctions could be considered an act of aggression, and their use of force seems far from proportionate. But while self-defense is certainly a just cause, it could be charged that Georgia provoked this attack, and if this is so, this raises significant problems, because just wars have to have a reasonable expectation of success. And given the significant civilian casualties, neither side seems to be showing the restraint necessary to limit civilian deaths.

Headlines:

- Georgia Fight Spreads, Moscow Issues Ultimatum (NYT)

- In Georgia and Russia, a Perfect Brew for a Blowup (NYT)

- Taunting the Bear (NYT)

- South Ossetian refugees head north to flee ruins of war (Guardian)

- Russia criticises US for flying Georgian troops back from Iraq (Guardian)

- Bush, Cheney Increasingly Critical of Russia Over Aggression in Georgia (Washington Post)

Thursday, August 07, 2008

Heroes, justice and “The Dark Night”

“You either die a hero or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain,” says Harvey Dent, the Gotham district attorney and “white knight” of this summer’s blockbuster hit, “The Dark Knight.”

“The Dark Knight,” of course, is full of violence and disturbing imagery, and in no way can it be considered a Catholic film, or even a Christian film. Yet, as Dent’s words reflect, the film asks an important question: How can we live in a world where radical injustice flourishes?

The same question vexed the prophet Jeremiah as he looked at the corruption of ancient Israel. “Go up and down the streets of Jerusalem, look around and consider, search through her squares,” God says to him. “If you can find but one person who deals honestly and seeks the truth, I will forgive this city” (5:1).

The fact that Jerusalem fell during Jeremiah’s lifetime shows how well the prophet’s search went, but Jeremiah’s failure reflects the gravity of the Christian understanding of the problem of justice: Because no one is without sin, no one can be considered truly just.

But if no one is just, where does that leave us? Batman and the Joker offer two different responses. For the Joker, the fact that no one is perfect is a constant invitation to show how imperfect people are. Everything becomes an experiment, in which he searches “good” people for their fatal flaws and then uses those flaws to destroy them.

The Joker is the ultimate cynic. For him, the values that tie a society together are just a whitewashed façade begging to be destroyed. “I took Gotham’s white knight, and brought him down to our level. It wasn’t hard,” the Joker says with glee. “All it takes is a little … push.”

The Joker is a disturbing character, not only because of his cruelty and insanity but also because he represents an increasingly prevalent element in contemporary society.

This weekend the New York Times Magazine published an article about hackers whose misanthropic hatred leads them to use the Internet to explode other people’s lives. [See earlier post.] One young man, the article says, was molested as a child, and so he channels his rage by engaging in emotional violence—harassing the parents of deceased children, for instance—to show people how rotten he thinks they truly are.

He defends himself by saying that it’s just how he has fun. So what if people’s lives are destroyed? After all, didn’t those worthless hypocrites have it coming?

As the Joker would say, “Why so serious?”

Or as Bruce Wayne’s servant Alfred would say, “Some men just want to watch the world burn.”

On the other hand, Batman reflects another answer. For him, the fact that justice is so rare and easily lost makes it all the more precious. Justice is a cause to be served, not a set of meaningless hypocrisies meant to be destroyed.

Following the path of justice in a cynical society is never easy. Jeremiah was mocked, harassed, beaten, imprisoned, and thrown down a well and left to die. And in the film, Batman is shocked at the level of hostility that his pursuit of justice causes among the people of Gotham. Ironically, the just man, in going against the grain of an unjust society, may be considered to be the antithesis of justice.

Yet, for all the back-dealing politicians, self-serving journalists, and two-timing cops, the people of Gotham, in the end, prove themselves worthy of Batman’s trust. This is the moral turning point of the film, the reason why the Joker loses and Batman wins.

And perhaps this moment of hope is the film’s answer to Jeremiah’s challenge. People sin, but their sinfulness never annuls their human dignity. The just person survives in the hope that as long as they struggle for justice and do not fall prey to cynicism, even the worst among us may show their true beauty and dignity as children of God. And that true justice—perfect justice—is not of this world, but eternal life.

Wednesday, August 06, 2008

Well, that just ain't kosher!

Working in an abattoir is never pretty, of course, but the working conditions here seemed to have been truly deplorable. "Children as young as 13 were said to be wielding knives on the killing floor," Shmuel Herzfeld writes in the New York Times today. "Some teenagers were working 17-hour shifts, six days a week." What is more, "the affidavit filed in the United States District Court of Northern Iowa," he continues, "alleges that an employee was physically abused by a rabbi on the floor of the plant."

All of this makes Herzfeld wonder: Is a plant that treats people this way truly kosher?

Within Jewish dietary law, the designation of "kosher" primarily applies to the selection and preparation of food. In a general sense, the rules are as follows:

- Certain animals may not be eaten at all. This restriction includes the flesh, organs, eggs and milk of the forbidden animals.

- Of the animals that may be eaten, the birds and mammals must be killed in accordance with Jewish law.

- All blood must be drained from the meat or broiled out of it before it is eaten.

- Certain parts of permitted animals may not be eaten.

- Fruits and vegetables are permitted, but must be inspected for bugs

- Meat (the flesh of birds and mammals) cannot be eaten with dairy. Fish, eggs, fruits, vegetables and grains can be eaten with either meat or dairy. (According to some views, fish may not be eaten with meat).

- Utensils that have come into contact with meat may not be used with dairy, and vice versa. Utensils that have come into contact with non-kosher food may not be used with kosher food. This applies only where the contact occurred while the food was hot.

- Grape products made by non-Jews may not be eaten.

- There are a few other rules that are not universal.

Yet, in addition to these dietary laws, Herzfeld emphasizes that the kosher tradition is inseparable from a concern for social justice. "Yisroel Salanter, the great 19th-century rabbi, is famously believed to have refused to certify a matzo factory as kosher on the grounds that the workers were being treated unfairly," he writes. Consequently, "in addition to the hypocrisy of calling something kosher when it is being sold and produced in an unethical manner, we have to take into account disturbing information about the plant that has come to light."

In purely practical terms, he notes, this makes sense: After all, if people are willing to flout labor regulations, how do we know that they aren't playing fast and loose with kosher laws? And how can a rabbi concentrate on making sure everything is kosher when he's too busy beating up the staff?

But Herzfeld reminds us that the kosher preparation of food reflects deeper concerns that resist an assembly line's demand for calculation and efficiency or an agribusiness's desire for profitability. To be kosher is to stand within a tradition that affirms the intrinsic value of persons and recognizes that there is something more important in life than meat on a plate.

Tuesday, August 05, 2008

On being Byronic

The great men of the past whose names have given an adjective to the language are by that very fact most vulnerable to the reductive treatment. Everybody knows what "Machiavellian" means, and "Rabelaisian"; everybody uses the terms "Platonic" and "Byronic" and relies on them to express certain commonplace notions in frequent use.The matter-of-fact tone of Barzun's opening line reminded me that much has changed since 1953. "Machiavellian" and "Platonic" are still in much use, but "Rabelaisian"—meaning "a style of satirical humour characterized by exaggerated characters and coarse jokes"—is much less so, perhaps depending on whether one has read Bakhtin recently. And the fates have been even less kind to "Byronic." A quick Google definition search of the term yields only a single, decidedly unhelpful entry—"Lord Byron (as in Byronic hero)"—that suggests that the word is perhaps as ill-used as it is misunderstood.

One of the interesting things about this particular essay is its awareness of how the relationship between the signifier "Bryonic" and the poet that the term signifies is constantly complicated and multi-layered. Does it refer to a "concentrated mind, and high spirits, wit, daylight good sense, and a passion for truth—in short a unique discharge of intellectual vitality"? A romantic, melancholy disposition borne of privilege and boredom? An active life as "a noble outlaw"? A wanton, pansexual eroticism? A scandalous, misunderstood existence as a self-imposed outcast? A sense of cynicism borne of out of an experence of real—or imagined—tragedy?

Of course, anyone who has been through high school or watched teen programming recently recognizes the contours of the Byronic sensibility, even though the posturing and angst of adolescence is never directly attached to the term. What makes the Byronic sensibility interesting, though, is the way in which the term has transcended the narrow confines of a dictionary definition to become a sort of genre of its own. There is only one way to be Machivellian, Platonic, or Rabelaisian, but being Byronic is as varied and complex as one wants it to be. And Byron himself would not have wanted it any other way.

Monday, August 04, 2008

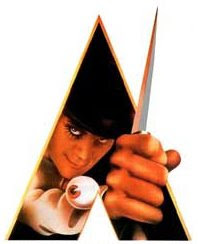

deeplydisturbing.org, .com, and .net

Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange, the famous dystopian book (and later movie with Malcolm McDowell) about youth culture run amok, is one of the most disturbing takes on postmodern life, not just because its content is disturbing but also because it has proved remarkably prophetic. While we may not be obsessed with Beethoven ("Ludwig van, baby!"), there's a certain eerie similarity about the trends in violence and popular culture that Burgess depicts and contemporary life, such as the use of "manscara" in Great Britain.

Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange, the famous dystopian book (and later movie with Malcolm McDowell) about youth culture run amok, is one of the most disturbing takes on postmodern life, not just because its content is disturbing but also because it has proved remarkably prophetic. While we may not be obsessed with Beethoven ("Ludwig van, baby!"), there's a certain eerie similarity about the trends in violence and popular culture that Burgess depicts and contemporary life, such as the use of "manscara" in Great Britain.Take, for instance, this graffiti that showed up spray-painted on the side of the Carnegie Library in Oakland:

Kinda funny, yes? Actually, vandalism is apparently the new poetry. The vandals have apparently read Eliot's "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," and it's on a library, so it's ironic, so I guess that makes it OK.

But perhaps the most disturbing trend is the growing presence of "trolls" on the web, people who perpetrate acts of emotional violence on the web for fun. As Mattathias Schwartz writes in The New York Times Magazine:

Measured in terms of depravity, insularity and traffic-driven turnover, the culture of /b/ has little precedent. /b/ reads like the inside of a high-school bathroom stall, or an obscene telephone party line, or a blog with no posts and all comments filled with slang that you are too old to understand.

The nadsat of the troll culture is a language of mysanthropic hatred that finds its jouissance in cruelty. But it's all in fun, so that makes it OK, too:

Welcome to the new fun.Thirty-two years old, he works “typical Clark Kent I.T.” freelance jobs — Web design, programming — but his passion is trolling, “pushing peoples’ buttons.” Fortuny frames his acts of trolling as “experiments,” sociological inquiries into human behavior. In the fall of 2006, he posted a hoax ad on Craigslist, posing as a woman seeking a “str8 brutal dom muscular male.” More than 100 men responded. Fortuny posted their names, pictures, e-mail and phone numbers to his blog, dubbing the exposé “the Craigslist Experiment.” This made Fortuny the most prominent Internet villain in America until November 2007, when his fame was eclipsed by the Megan Meier MySpace suicide. Meier, a 13-year-old Missouri girl, hanged herself with a belt after receiving cruel messages from a boy she’d been flirting with on MySpace. The boy was not a real boy, investigators say, but the fictional creation of Lori Drew, the mother of one of Megan’s former friends. Drew later said she hoped to find out whether Megan was gossiping about her daughter. The story — respectable suburban wife uses Internet to torment teenage girl — was a media sensation.

Friday, August 01, 2008

Harry Potter and Children's Orphanages

A recent study found that adults who had grown up in institutions were:

- 10 times more likely than the general population to be trafficked abroad for

the purposes of sexual exploitation;- 30 times more likely to become an alcoholic;

- 45 times more likely to be unemployed or in insecure employment;

- more than 100 times more likely to have a criminal record; and

- 500 times more likely to kill themselves

Thursday, July 31, 2008

Newsflash: Music doesn't pay well

I had always thought of music education at the K-12 level as dull and unchallenging, work fit for music majors who couldn't cut it in performance, theory, or musicology. However, faced with a tanking economy and three empty years on the academic-job circuit, I'm learning to swallow my pride and re-evaluate being a schoolteacher. It's still not my idea of a great job, but again, it pays.

Wednesday, July 30, 2008

My vote is for Schopenhauer

And this, according to the World Congress of Philosophers website, is precisely what the event is about:

The first World Congress to be held in Asia, the Seoul Congress presents a clear invitation to rethink the nature, roles, and responsibilities of philosophy and of philosophers in the age of globalization. It is committed to paying heed to the problems, conflicts, inequalities, and injustices connected with the development of a planetary civilization that is at once multicultural and techno-scientific.The topics are serious, and so is the intent. As Julian Baggini writes in the Guardian:

The official line seems to be that the world somehow needs philosophy if it is to deal with its great problems. In the first of four "congratulatory addresses," Han, the prime minister, said he thought it could help both environmental problems and the fight against terror. Lee Jang-moo, the president of Seoul National University, claimed it could teach us "the direction in which to steer the human destiny." Such hopes for philosophy are shared in high places: Koïchiro Matsuura, the director general of Unesco, told the congress, via video, about how Unesco was committed to fostering the teaching of philosophy around the world. He wasn't just being polite: Unesco even has a "philosophy strategy."While we need, as Hannah Arendt aptly put it, "to think what we are doing" now more than ever, there is a sense of elitism here, a sense that philosophers, by their professional training, are entitled to speak and perhaps—as the name "congress" implies—even to rule. The philosopher king may be Plato's ideal, but it also suggests that ideas are somehow separate from the practice of daily life and from those not suitably "trained" to engage in complex thought.

But as anyone who studies rhetoric knows, ideas always have consequences, and people of all ages, educational levels, and IQs trade in ideas on a daily basis. To abstract intellectual life into the realm of the intelligensia both neglects this fact and, perhaps more important, keeps philosophers from learning about the fullness of the human experience—which, in the end, is ultimately what philosophy is about. Julian Baggini again:

If philosophy is indeed important, it is because it is not the preserve of philosophers. The professionalisation of the subject has disguised this once obvious fact. In the UK, for example, it is often thought philosophy is not an important part of the culture, but it's actually all over the place: in serious journalism, the work of thinktanks, and in ethics committees. It's just not usually called "philosophy." Indeed, if you want to be taken seriously, you'd be advised not to use the p-word at all. Oliver Letwin, for example, has a PhD in philosophy and has published a book on the subject, but he once told me in an interview that it would hinder, not help him, if more people knew this. (Sorry, Olly.)

So if we are to rethink philosophy, we should rethink first and foremost what it is and how it does and should inform wider debate. Those who have earned the title "philosopher" need to both accept that those who have not are equal participants in such a discussion, which also means being more willing to engage as equals in it.

Tuesday, July 29, 2008

Ode to Scrabulous

Hasbro, who owns the copyright to Scrabble in the United States and Canada, filed a lawsuit against the creators of the game, Rajat and Jayant Agarwalla of Calcutta, on July 24. This morning, American and Canadian visitors to Facebook expecting to play (yours truly included) found that their access had been blocked.

The story began in January of this year, when Hasbro approached Facebook and asked them to remove the application from the site. That strategy failed, since Scrabulous was neither developed nor owned by Facebook but merely placed there by the Agarwalla brothers like thousands of other applications posted to the site.

Scrabulous, like the millions of other applications floating around on the web, as something of an experiment. The only difference was its massive popularity. Rory Cellan-Jones, the BBC's technology correspondent, remarked in January that the Agarwallas were making something like $25,000 a month off of advertising revenues, and this success, while a pittance in comparison to the value of Facebook itself, was enough to spark the attention and the ire of Hasbro. "The early dreams of being a happy-clappy, open-source, 'do no evil' kind of business soon fade when the realisation dawns that you are worth suing," wrote Cellan-Jones.

Monday, July 28, 2008

Reading in the age of the Internet

The issue isn't that young people aren't reading, but that they're reading in different ways.A slender, chatty blonde who wears black-framed plastic glasses, Nadia checks her e-mail and peruses myyearbook.com, a social networking site, reading messages or posting updates on her mood. She searches for music videos on YouTube and logs onto Gaia Online, a role-playing site where members fashion alternate identities as cutesy cartoon characters. But she spends most of her time on quizilla.com or fanfiction.net, reading and commenting on stories written by other users and based on books, television shows or movies.

Her mother, Deborah Konyk, would prefer that Nadia, who gets A’s and B’s at school, read books for a change. But at this point, Ms. Konyk said, “I’m just pleased that she reads something anymore.”

Reading in print and on the Internet are different. On paper, text has a predetermined beginning, middle and end, where readers focus for a sustained period on one author’s vision. On the Internet, readers skate through cyberspace at will and, in effect, compose their own beginnings, middles and ends.Whatever side one takes on the relationship between literacy and the Internet—and there is significant debate as to whether these young people are even "literate" at all—the changes that the Internet has brought to reading habits are here to stay, and they reflect more fundamental changes in what constitutes a "text."

In a world defined—some would say "disciplined"—by the technology of the printing press, the eye is taught to follow a line of printed words, one after the other, from beginning to end. But the Internet creates a new type of textuality defined by what the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze calls the rhizome. In botany, a "rhizome" is a root plant that creates dense networks of shoots and nodes. Unlike a tree, whose root structure is much more centralized and hierarchical, rhizomes are dynamic and decentralized. Instead of fulfilling a prearranged "plan," they "happen."

Deleuze and Félix Guattari's 1980 collaboration A Thousand Plateaus applied the rhizome to reading. Breaking with "arborescent" reading patterns, they used the metaphor to view texts not as linear arguments that need to be grounded and followed methodically from beginning to end but as dynamic entities that can be entered, understood, broken apart, and repackaged in a multitude of ways. In what would have been a radical move for the time, they remarked that their book wasn't intended to be read straight-through, and they invited readers to pick and choose what they wanted to read and discard the parts they didn't find useful.

Though they may not have known it at the time, Deleuze and Guattari were describing the cultural and intellectual condition of the Internet age, in which knowledge isn't created by a single author and centrally disseminated but is a common project built by many hands.

Of course, this transition is both a blessing and a curse. While the new intellectual culture of reading and textual engagement is dynamic and playful, it also runs the risk of losing track of its grounding. Part of the joy of traditional reading lies in the ways in which it forces readers to go through parts that are at first glance "unnecessary" or "boring" but contribute to the understanding of the whole. Deleuze and Guattari, grounded in the tradition of Western philosophy and metaphysics, may have found the rhizome a welcome release, but for a younger generation who may never sit down and read the ideas that they bounce back and forth on-line, the freedom of the rhizome may be experienced as a sort of intellectual chaos.