Thursday, August 07, 2008

Heroes, justice and “The Dark Night”

“You either die a hero or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain,” says Harvey Dent, the Gotham district attorney and “white knight” of this summer’s blockbuster hit, “The Dark Knight.”

“The Dark Knight,” of course, is full of violence and disturbing imagery, and in no way can it be considered a Catholic film, or even a Christian film. Yet, as Dent’s words reflect, the film asks an important question: How can we live in a world where radical injustice flourishes?

The same question vexed the prophet Jeremiah as he looked at the corruption of ancient Israel. “Go up and down the streets of Jerusalem, look around and consider, search through her squares,” God says to him. “If you can find but one person who deals honestly and seeks the truth, I will forgive this city” (5:1).

The fact that Jerusalem fell during Jeremiah’s lifetime shows how well the prophet’s search went, but Jeremiah’s failure reflects the gravity of the Christian understanding of the problem of justice: Because no one is without sin, no one can be considered truly just.

But if no one is just, where does that leave us? Batman and the Joker offer two different responses. For the Joker, the fact that no one is perfect is a constant invitation to show how imperfect people are. Everything becomes an experiment, in which he searches “good” people for their fatal flaws and then uses those flaws to destroy them.

The Joker is the ultimate cynic. For him, the values that tie a society together are just a whitewashed façade begging to be destroyed. “I took Gotham’s white knight, and brought him down to our level. It wasn’t hard,” the Joker says with glee. “All it takes is a little … push.”

The Joker is a disturbing character, not only because of his cruelty and insanity but also because he represents an increasingly prevalent element in contemporary society.

This weekend the New York Times Magazine published an article about hackers whose misanthropic hatred leads them to use the Internet to explode other people’s lives. [See earlier post.] One young man, the article says, was molested as a child, and so he channels his rage by engaging in emotional violence—harassing the parents of deceased children, for instance—to show people how rotten he thinks they truly are.

He defends himself by saying that it’s just how he has fun. So what if people’s lives are destroyed? After all, didn’t those worthless hypocrites have it coming?

As the Joker would say, “Why so serious?”

Or as Bruce Wayne’s servant Alfred would say, “Some men just want to watch the world burn.”

On the other hand, Batman reflects another answer. For him, the fact that justice is so rare and easily lost makes it all the more precious. Justice is a cause to be served, not a set of meaningless hypocrisies meant to be destroyed.

Following the path of justice in a cynical society is never easy. Jeremiah was mocked, harassed, beaten, imprisoned, and thrown down a well and left to die. And in the film, Batman is shocked at the level of hostility that his pursuit of justice causes among the people of Gotham. Ironically, the just man, in going against the grain of an unjust society, may be considered to be the antithesis of justice.

Yet, for all the back-dealing politicians, self-serving journalists, and two-timing cops, the people of Gotham, in the end, prove themselves worthy of Batman’s trust. This is the moral turning point of the film, the reason why the Joker loses and Batman wins.

And perhaps this moment of hope is the film’s answer to Jeremiah’s challenge. People sin, but their sinfulness never annuls their human dignity. The just person survives in the hope that as long as they struggle for justice and do not fall prey to cynicism, even the worst among us may show their true beauty and dignity as children of God. And that true justice—perfect justice—is not of this world, but eternal life.

Wednesday, August 06, 2008

Well, that just ain't kosher!

Working in an abattoir is never pretty, of course, but the working conditions here seemed to have been truly deplorable. "Children as young as 13 were said to be wielding knives on the killing floor," Shmuel Herzfeld writes in the New York Times today. "Some teenagers were working 17-hour shifts, six days a week." What is more, "the affidavit filed in the United States District Court of Northern Iowa," he continues, "alleges that an employee was physically abused by a rabbi on the floor of the plant."

All of this makes Herzfeld wonder: Is a plant that treats people this way truly kosher?

Within Jewish dietary law, the designation of "kosher" primarily applies to the selection and preparation of food. In a general sense, the rules are as follows:

- Certain animals may not be eaten at all. This restriction includes the flesh, organs, eggs and milk of the forbidden animals.

- Of the animals that may be eaten, the birds and mammals must be killed in accordance with Jewish law.

- All blood must be drained from the meat or broiled out of it before it is eaten.

- Certain parts of permitted animals may not be eaten.

- Fruits and vegetables are permitted, but must be inspected for bugs

- Meat (the flesh of birds and mammals) cannot be eaten with dairy. Fish, eggs, fruits, vegetables and grains can be eaten with either meat or dairy. (According to some views, fish may not be eaten with meat).

- Utensils that have come into contact with meat may not be used with dairy, and vice versa. Utensils that have come into contact with non-kosher food may not be used with kosher food. This applies only where the contact occurred while the food was hot.

- Grape products made by non-Jews may not be eaten.

- There are a few other rules that are not universal.

Yet, in addition to these dietary laws, Herzfeld emphasizes that the kosher tradition is inseparable from a concern for social justice. "Yisroel Salanter, the great 19th-century rabbi, is famously believed to have refused to certify a matzo factory as kosher on the grounds that the workers were being treated unfairly," he writes. Consequently, "in addition to the hypocrisy of calling something kosher when it is being sold and produced in an unethical manner, we have to take into account disturbing information about the plant that has come to light."

In purely practical terms, he notes, this makes sense: After all, if people are willing to flout labor regulations, how do we know that they aren't playing fast and loose with kosher laws? And how can a rabbi concentrate on making sure everything is kosher when he's too busy beating up the staff?

But Herzfeld reminds us that the kosher preparation of food reflects deeper concerns that resist an assembly line's demand for calculation and efficiency or an agribusiness's desire for profitability. To be kosher is to stand within a tradition that affirms the intrinsic value of persons and recognizes that there is something more important in life than meat on a plate.

Tuesday, August 05, 2008

On being Byronic

The great men of the past whose names have given an adjective to the language are by that very fact most vulnerable to the reductive treatment. Everybody knows what "Machiavellian" means, and "Rabelaisian"; everybody uses the terms "Platonic" and "Byronic" and relies on them to express certain commonplace notions in frequent use.The matter-of-fact tone of Barzun's opening line reminded me that much has changed since 1953. "Machiavellian" and "Platonic" are still in much use, but "Rabelaisian"—meaning "a style of satirical humour characterized by exaggerated characters and coarse jokes"—is much less so, perhaps depending on whether one has read Bakhtin recently. And the fates have been even less kind to "Byronic." A quick Google definition search of the term yields only a single, decidedly unhelpful entry—"Lord Byron (as in Byronic hero)"—that suggests that the word is perhaps as ill-used as it is misunderstood.

One of the interesting things about this particular essay is its awareness of how the relationship between the signifier "Bryonic" and the poet that the term signifies is constantly complicated and multi-layered. Does it refer to a "concentrated mind, and high spirits, wit, daylight good sense, and a passion for truth—in short a unique discharge of intellectual vitality"? A romantic, melancholy disposition borne of privilege and boredom? An active life as "a noble outlaw"? A wanton, pansexual eroticism? A scandalous, misunderstood existence as a self-imposed outcast? A sense of cynicism borne of out of an experence of real—or imagined—tragedy?

Of course, anyone who has been through high school or watched teen programming recently recognizes the contours of the Byronic sensibility, even though the posturing and angst of adolescence is never directly attached to the term. What makes the Byronic sensibility interesting, though, is the way in which the term has transcended the narrow confines of a dictionary definition to become a sort of genre of its own. There is only one way to be Machivellian, Platonic, or Rabelaisian, but being Byronic is as varied and complex as one wants it to be. And Byron himself would not have wanted it any other way.

Monday, August 04, 2008

deeplydisturbing.org, .com, and .net

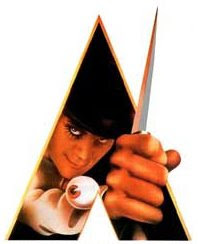

Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange, the famous dystopian book (and later movie with Malcolm McDowell) about youth culture run amok, is one of the most disturbing takes on postmodern life, not just because its content is disturbing but also because it has proved remarkably prophetic. While we may not be obsessed with Beethoven ("Ludwig van, baby!"), there's a certain eerie similarity about the trends in violence and popular culture that Burgess depicts and contemporary life, such as the use of "manscara" in Great Britain.

Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange, the famous dystopian book (and later movie with Malcolm McDowell) about youth culture run amok, is one of the most disturbing takes on postmodern life, not just because its content is disturbing but also because it has proved remarkably prophetic. While we may not be obsessed with Beethoven ("Ludwig van, baby!"), there's a certain eerie similarity about the trends in violence and popular culture that Burgess depicts and contemporary life, such as the use of "manscara" in Great Britain.Take, for instance, this graffiti that showed up spray-painted on the side of the Carnegie Library in Oakland:

Kinda funny, yes? Actually, vandalism is apparently the new poetry. The vandals have apparently read Eliot's "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," and it's on a library, so it's ironic, so I guess that makes it OK.

But perhaps the most disturbing trend is the growing presence of "trolls" on the web, people who perpetrate acts of emotional violence on the web for fun. As Mattathias Schwartz writes in The New York Times Magazine:

Measured in terms of depravity, insularity and traffic-driven turnover, the culture of /b/ has little precedent. /b/ reads like the inside of a high-school bathroom stall, or an obscene telephone party line, or a blog with no posts and all comments filled with slang that you are too old to understand.

The nadsat of the troll culture is a language of mysanthropic hatred that finds its jouissance in cruelty. But it's all in fun, so that makes it OK, too:

Welcome to the new fun.Thirty-two years old, he works “typical Clark Kent I.T.” freelance jobs — Web design, programming — but his passion is trolling, “pushing peoples’ buttons.” Fortuny frames his acts of trolling as “experiments,” sociological inquiries into human behavior. In the fall of 2006, he posted a hoax ad on Craigslist, posing as a woman seeking a “str8 brutal dom muscular male.” More than 100 men responded. Fortuny posted their names, pictures, e-mail and phone numbers to his blog, dubbing the exposé “the Craigslist Experiment.” This made Fortuny the most prominent Internet villain in America until November 2007, when his fame was eclipsed by the Megan Meier MySpace suicide. Meier, a 13-year-old Missouri girl, hanged herself with a belt after receiving cruel messages from a boy she’d been flirting with on MySpace. The boy was not a real boy, investigators say, but the fictional creation of Lori Drew, the mother of one of Megan’s former friends. Drew later said she hoped to find out whether Megan was gossiping about her daughter. The story — respectable suburban wife uses Internet to torment teenage girl — was a media sensation.